Traditional Sequential Intercept Model

The traditional Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) identifies five points or intercepts along the criminal justice continuum where an intervention can prevent individuals with mental illness from becoming more enmeshed in the criminal justice system.

Intercept Zero

Policy Research Associates, which supports the operation of SAMHSA’s GAINS Center, has introduced “Intercept 0” to its SIM model. This is in response to recent County and Statewide initiatives that provide earlier intervention services to individuals with mental illness in the effort to prevent criminal justice involvement. “The goal of Intercept 0 is to align systems and services and connect individuals in need with treatment before a behavioral health crisis begins or at the earliest possible stage of system interaction.” (Policy Research Associates Intercept Zero Infographic, 2016)2

Download the full .pdf explaining the Intercept Zero concept.

In the early 1990’s there was a growing recognition of the over representation of individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) in the criminal justice system. The reasons for this increase were myriad including the growing de-institutionalization movement, legislative fiscal decisions that cut or did not grow resources to meet the increased need, new Policing policies, and new sentencing guidelines. The criminal justice system was not prepared for, nor was it trained to deal with, the increase of those with a mental illness in the system. The problem continues with correctional institutions in the United States having become the largest individual providers of mental health care in the country.

The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) was created to give a framework for government entities to look at community based alternatives to arrest or continued imprisonment of individuals with SMI. It identifies the points in an ideal system where services could be placed to intervene or intercept the individual with SMI. The SIM is a basic starting point for discussions regarding what services could be in place and where in the system they should be.

The traditional Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) identifies five points or intercepts along the behavioral health/criminal justice continuum where an intervention can prevent individuals with mental illness from entering or becoming more enmeshed in the criminal justice system.[1] (Munetz and Griffin, 2006)

The initial framework of SIM looked at what options were possible or recommended. It was the beginning of the discussion and focused on what could or should be. The Cross Systems Mapping (CSM) was an early evolution of the SIM. It is a workshop based tool that assists County Behavioral Health and Criminal Justice Systems to develop cross system collaboration and identify the services they already have available, identify unmet needs in the system, set priorities, and develop plans for creating services to achieve those priorities. It looks at the current state of the system, what’s missing and jumpstarts the discussion regarding what services are needed. [2] (Griffin and others, 2015)

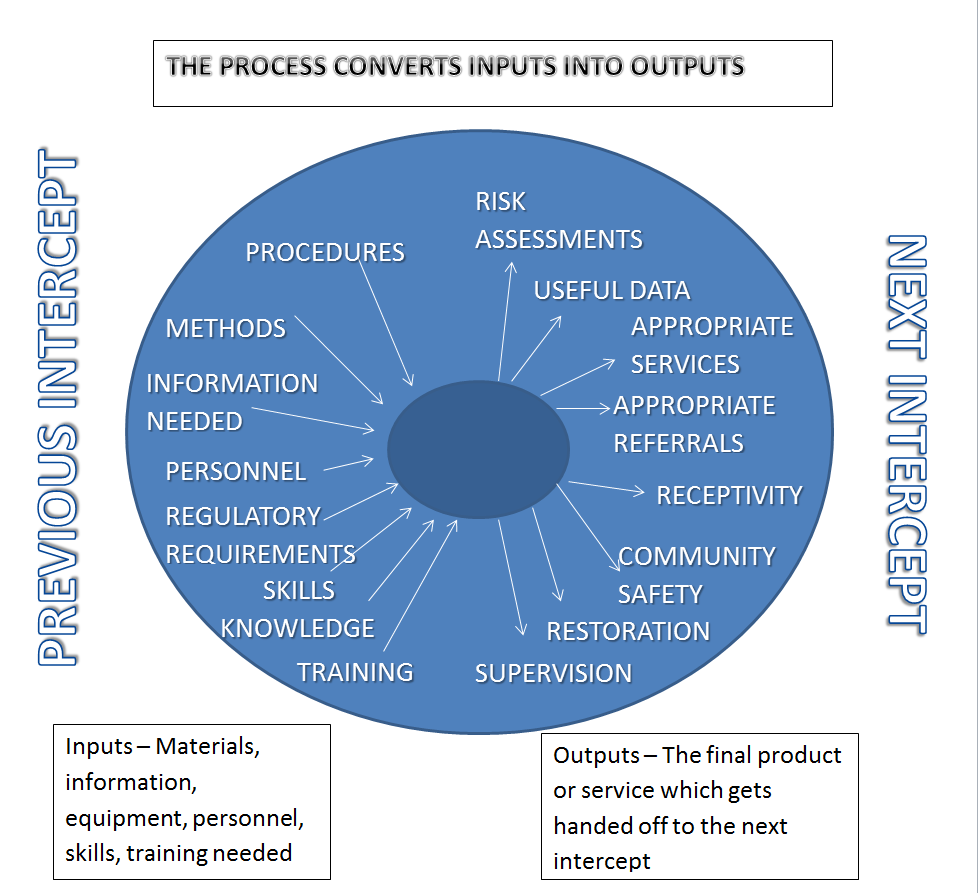

One of the latest evolutions in the SIM is the Forensic System Process Mapping (FSPM). While the SIM focuses on where agencies are placed within the BH/CJ system and the CSM focuses on what’s missing in the system, the FSPM focuses on how the system interacts with the individual. It focuses on how a person transits between each of the intercepts and how those agencies involved in each intercept function. In general terms the FSPM defines the mission of each agency and Identifies what’s needed for achieving that mission. It outlines the process used to achieve the mission and describes the steps used in the process. It explains the order of the steps, the activities of the steps and the personnel, information, and equipment needed to complete each step.

The FSPM identifies:

The methods the team uses to gather this information include:

The FSPM defines what success looks like for each agency involved in the transit between intercepts. Although the transit points follow the intercept model they are broken down into stages that emphasize the transition between the intercepts. The stages include:

Information is gathered that describes the system and how it interacts with the individuals it serves. The process creates a product. That product costs time, money and energy. It changes the lives of all it serves and affects entire communities. The FSPM looks at the process and system as is, not as it should be. It does not critique or find fault. The report does not make recommendations. The completed report is sent to the Problem Solving Collaborative (described below) for review, discussion and recommendations. FSS believes strongly that all decisions and recommendations should be made locally and collaboratively. FSS consultants are available to assist in making recommendations as described below.

The FSPM also meets all the requirements of the Stepping Up Initiative Question 4. “Have you conducted a comprehensive process analysis and service inventory?” FSS works with Counties working through the “6 questions” of the Stepping Up Initiative as well.

An essential part of the FSPM is the development of a local collaborative Problem Solving group. The PSC is made up of key agency leadership personnel and court representatives with enough decision making power to orchestrate change in the system. This group reviews the mapping, identifies areas that can be improved upon, and develops a plan for that improvement. The PSC sets its goal as Whole System Improvement. It becomes responsible for the success of any changes, even if those changes are to occur within one or two separate agencies. This collaborative effort stops the defensiveness that comes from finger pointing and allows the system to bring all needed resources together for a whole system win. Envision a relay team deciding to assist one team member in improving their handoff skills. The whole team becomes more successful at what they do with the improvement of that one member. This allows for a more efficient division of resources and support. Consultants from FSS can be involved with the PSC to offer recommendations at this point including information on Evidence Based Practice and Best Practice alternatives.

In many counties that group is part of a larger collaborative group that is focused on the BH and CJ system. The Criminal Justice Advisory Board (CJAB) or the Forensic Interagency Task Force (FITF) are 2 typical homes for the PSC.

Here’s an example. (Although this example is exaggerated to some degree examples like these are common in smaller degrees in most systems.) Henry had been arrested and detained for Disorderly Conduct. He was outside a local convenience store yelling at passers-by and customers. When asked to leave he started yelling at the store owner. When the Police asked Henry to leave he started yelling at them. The decision was made to arrest him because of his abusive language, refusal to stop yelling, refusal to cooperate with police and not giving personal information besides his name.

At Central Booking, he again was not cooperative in giving personal information including his address. His bail was set at $600. He did not have the needed $60 for a bail bond nor was he supplying a stable address so was detained in the county prison. After several days in jail it was determined that he had a serious mental illness but was not able to see a psychiatrist and be started on an anti-psychotic for three weeks. It was necessary to have him evaluated for competency to assist in his defense. The medications began helping him toward competency and he started sharing additional information. There were no assessments available to assess his needs for treatment besides medications or to assess his criminogenic risk factors. Even though it was later determined that he had stable supportive housing options and ongoing treatment he did not have a source for the $60 bail bond. Henry went to trial, pled guilty and was sentenced to time served. A forensic case manager from the County became involved and set up his old treatment and housing support. He was discharged from the jail with appointments for follow up at his previous treatment provider but with only three days medication. Henry spent five months in the local jail at the cost of $13,920 to the county taxpayers.

Unrelated to Henry a System Process Mapping was requested by the County CJAB and completed six months later. The County Prison was overcrowded and the County was exploring options. Diversions, renovating the existing prison, renting room in other county jails, or building a new prison were options being explored. Interviews and protocol reviews were held with both leadership and direct service personnel with the County Behavioral Health entity, the Police Department, the Booking Center, Magisterial District Judges, Pre-Trial Services, Public Defenders, District Attorneys’ Office, Court of Common Pleas Personnel and Judges, and the Prison Correctional and Medical Staff.

The FSPM revealed that a lot of good work was being done in the system and that most routine cases were handled well. Among the other issues found were: The County had a small CIT program but only 5% of officers had been trained. There was no other type of training that identified signs of mental illness or diversion options available. Typical protocol dictated that officers be trained exclusively in the Ask-Tell-Make philosophy when dealing with uncooperative subjects. The Booking Center used an intake assessment that relied solely on subject report for mental health, substance use and used minimal Officer inputs. Use of the assessment tool was very inconsistent based on personnel, shift and level of cooperation of subject. MDJ’s were not trained in recognizing MI and diversion options. There was a cash bail system in place with no pre-trial alternatives and risk analysis instruments in place. There was not a fund for bail for the indigent. There had been one but it was abused a number of years ago and was ended. Once in the jail it took 3 weeks to see a psychiatrist unless there was a known history or “clear signs” of serious and dangerous mental illness and another week to begin medications. Competency evaluations averaged a one month wait but hospitalization for Competency Restoration had a waiting list of eight to 14 months. CO staff had minimal training in recognizing signs of MI and De-escalation. Pre-Trial Services did not have a way of checking status with the local MH Agency without subjects permission. Although a protocol for notifications existed reports to the County MH Administrator on admissions to the prison were sporadic and not reviewed well.

During the Cross Systems Mapping it was reported that there was a CIT program and communication between local police and county behavioral health, there were protocols in place for diversion activities, there were assessments at the Booking Center that focused on the individuals ability to function in prison and mental status, there was MH care available in the prison and communication between the prison and the County BHU. Although this was true, those services were poor in quality and inconsistently applied.

This information was delivered to the County CJAB. As a collaborative body they chose to focus additional resources on pre-trial initiatives, especially utilizing Evidence Based Programs. The CIT program was reenergized. Additional work was done on restarting the indigent bail fund with improved protocols, developing other risk needs based alternatives to cash bail and developing a standardized training regime for all system personnel. The system improved collaboration between the BH system and CJ with the development of a Forensic Task Force.

This type of FSPM allows for more collaborative decision making on initiatives that affect the whole system, the sharing of resources, less blaming of individual agencies and achieving county wide goals.

[1] Munetz, M.R. & Griffin, P.A. (2006). Use of the Sequential Intercept Model as an approach to decriminalization of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57(4), 544-549.

[2] Griffin, P., LaDuke, C., Abreu, D., Winckworth-Prejsnar, K., Filone, S., Dorrel, S., Finello, C., (2015) Usig the SIM in Cross System Mapping In Griffin, P., Heilbrun, K., Mulvey, E., DeMatteo, D., Schubert, C (2015) The Sequential Intercept Model and Criminal Justice (pp. 239-256) NY, NY Oxford University Press